Maine aquaculturists have been raising salmon since the 1970s. Hatcheries throughout the state (some as far inland as Bingham and Oquossoc) produce 3-4 million fish each year for net-pen operations along the coast. The Atlantic salmon is an anadromous species, spending part of its time in fresh water and part in salt water. In the wild, most of an adult salmon’s life is spent in the ocean. During the spring of the fourth or fifth year, the adult fish will return to its river of origin to spawn. After about two or three years in fresh water, young fish will go through a physiological change known as smoltification, which makes the fish ready for life in the sea.

The steelhead has been domesticated for 150 years, much longer than the Atlantic salmon. The optimal temperature range for the steelhead is higher than for the Atlantic salmon, but since the life cycles of the two species of fish are so similar, producers often grow them together.

The steelhead has been domesticated for 150 years, much longer than the Atlantic salmon. The optimal temperature range for the steelhead is higher than for the Atlantic salmon, but since the life cycles of the two species of fish are so similar, producers often grow them together.

In salmonid farms, some adult, four-year-old fish are reserved for broodstock. Spawning occurs between mid-November and mid-December. A 12- pound female fish produces an average of 10,000 eggs each season, which are fertilized and then incubated at a freshwater hatchery. The eggs hatch and eventually grow into free-swimming fry. When fry develop dark vertical bands on their sides during the first year of life, they are called parr. For the first 18 months of their life cycle in the hatchery, parr are graded, vaccinated against diseases, and their health and growth monitored. After 18 months in the hatchery in fresh water, young salmon undergo major changes that enable them to live in salt water. Their kidneys adapt to excrete salt, rather than retain it. Their skin becomes silvery so the fish will be less visible to predators in the ocean. Changes also occur in the eyes, blood plasma, musculature, and fat. This process is called smoltification. The smolts, roughly five inches long, are transferred to floating pens in the sea, typically between mid-April and mid-May.

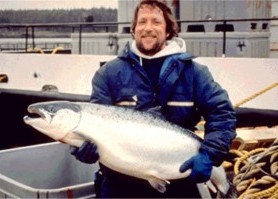

Net pens are typically 30 to 50 feet deep, and are moored using large anchors and rope grid systems. During their ocean growout phase fish are fed pellets of made of fish meal, fish oil, plant proteins and vitamins, and minerals. To maintain their health and help them fight off naturally occurring diseases all smolts are health tested and vaccinated prior to transfer to the ocean pens. After two years in the ocean pens, fish grow from smolts weighing 3-5 oz. (80-120 grams) to fish with a market weight of 6-12 pounds. When they reach marketable size, the fish are harvested, cleaned, iced, and shipped to customers. Salmon and steelhead raised in Maine are harvested on demand and delivered fresh to the customer within 24-36 hours.

Saltwater grow-out sites are located primarily in Washington and Hancock counties, where excellent water quality, protected bays, water temperatures of 0-15C ( 32- 59F), strong currents, and high tides provide ideal conditions for raising salmon. With ideal environmental conditions and some of the strictest state and federal environmental regulations and monitoring requirements in the world Maines farmed salmon are produced using sustainable methods in a clean healthy ecosystem.

Salmon farmers in Maine were some of the first in the world to develop a series of Best Management Practices (BMPs) designed to minimize their environmental footprint while they produce healthy sustainable food. Developed in cooperation with State and Federal regulators and the environmental community the BMPs establish environmental goals over and above those required by regulation and use external audits to demonstrate compliance. In addition all Maine salmon farming companies participate in the Global Aquaculture Alliance Best Aquaculture Practices program, and the Maine Aquaculture Associations Code of Practice, Bay Management and Biosecurity programs. All of these programs establish additional operational and monitoring requirements. A number of them also include extensive third party audits to verify compliance.

Salmon farmers in Maine were some of the first in the world to develop a series of Best Management Practices (BMPs) designed to minimize their environmental footprint while they produce healthy sustainable food. Developed in cooperation with State and Federal regulators and the environmental community the BMPs establish environmental goals over and above those required by regulation and use external audits to demonstrate compliance. In addition all Maine salmon farming companies participate in the Global Aquaculture Alliance Best Aquaculture Practices program, and the Maine Aquaculture Associations Code of Practice, Bay Management and Biosecurity programs. All of these programs establish additional operational and monitoring requirements. A number of them also include extensive third party audits to verify compliance.

Maine’s salmon farmers use a bay management, site rotation and fallowing program that results in a natural 3 year cycle of production levels. Depending on the year, number of farms in production and environmental conditions production varies with farm gate values ranging between 65 and 85 million dollars annually. For economically depressed rural communities and traditional working waterfronts facing fisheries collapses this economic activity has been a vital help in maintaining local communities and diversifying their economic base. Increasingly traditional fishing families who have lost their access to traditional fisheries due to license or resource restrictions are turning to aquaculture to continue their maritime heritage.